Though some might be embarrassed to admit it, I have no qualms with telling you that I usually choose the books I read by their covers. If the illustration speaks to me in some way through its use of color, tone, and type, then I’ll flip to the first page and preview the writing style. If not, then I’ll move on to the next cover, etc, until I find something that connects both with my interests and the mood I happen to be in.

My go-to genre of choice is dark fantasy, that sub-genre of fantasy where evil is much more predominant, the tone is more ominous, themes tend to be more frightening, and the plot is often more violent. Covers for these books tend to reflect their nature with deeper, darker colors, depictions of weapons, and fonts that are more chiseled or jagged. When the cover designs feature characters, those figures are often cloaked in shadow or dressed for battle and bedecked with the kinds of weapons that ensure any fighting will be up close and personal.

For example,

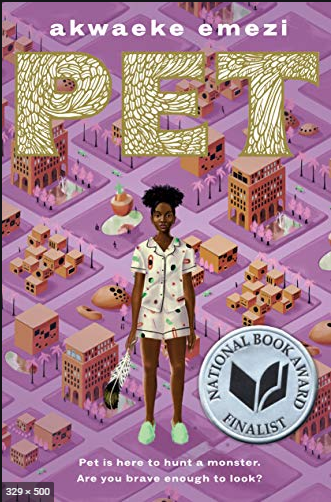

By contrast, the illustration on the cover of Akwaeke Emezi’s novel Pet is innocently whimsical, a bit surreal, and very far from the dark, swirling, ominous covers that grab my attention. So, it is likely not surprising to hear me say that I would not have chosen to read Emezi’s YA by its cover.

Instead of a design that portends violence, the cover of Pet features a pajama-clad black teen holding a feather and standing at the forefront of a purple and pink grid of streets and building complexes. The title of the novel is printed in a very large, feather-textured font that is outlined in gold.

Aside from its brighter, more holistic vibe, for me, a middle-aged, white woman, I find very little depicted here that I can relate to.

- I’m not a black teen, and the number of years since I was a teen is not one I’d like to reflect on at the moment.

- I don’t do fuzzy slippers. Or slippers at all for that matter.

- Pink and purple are, at least presently, my least favorite colors. (As a teen, my entire bedroom was Pepto Bismol pink, and I do mean my entire bedroom. To say I went through a pink phase would be an understatement. It would be more accurate to say I burned through a pink phase and to this day remain on pink burnout.)

- And, I categorize feathers along with sequins, sparkles, lace, and other equally frivolous and functionless accouterments that scream “Hey! Look at me!!” Please don’t, thank you very much! (Another flashback, this time to my prom dress which was, you guessed it, pink with a ton of lace…)

Granted, the National Book Award Finalist seal on Pet’s cover would have given me pause, but likely just a small one. That is why I am forever grateful that I was put in a position where I had no choice but to read Emezi’s novel.

Here are reasons why everyone, even adults, who might have passed over this YA book for similarly biased reasons of their own should definitely read it…NOW.

- Pet forces the reader to confront the impact that various tropes and assumptions have on our collective consciousness.

Close your eyes and picture it, if you’re brave enough. What does a monster look like to you?

Does it have red, demonic eyes? Horns? A forked tongue? Or maybe a spiked tail? Is your monster inhumanly tall? Or shrouded in a dark fog? Does it speak? Is its voice raspy, or hiss-like? Or, maybe it communicates by invading your mind?

Chances are a good number of us would imagine a monster with striking similarities or at the very least a variation on this familiar trope. So, I guess it’s safe to say that we adults know what a monster looks like. Or do we?

This is the first question the reader is confronted with when reading Pet. What do real monsters look like? An answer is explicitly provided in the first chapter of the novel.

| Monsters don’t look like anything…That’s the whole point. That’s the whole problem. ~Akwaeke Emezi, Pet, p.12 |

With this unsettling truth, Emezi then carefully constructs a story that repeatedly confronts the reader with opportunities to experience and examine this truth.

Lucille, the town in which Pet takes place, believes to have eradicated its monsters through revolution. Among the list of these monsters are government officials, teachers, and police officers. Among the list of monstrous deeds are school shootings, monuments to slaveholders, and religious elitism. One can not help but see the parallels between the problems of the old Lucille and the state of our current society.

Monsters are people. And, monsters are scary because they can’t be identified by what they look like. The veracity of these statements is proven through the reader’s experience.

Jam, the protagonist, is aided in her search to uncover a monster in her best friend’s house by Pet, a creature that might have stepped straight out of a childhood nightmare. Pet is described as having goat legs, a twisted torso, thick white fur that was streaked with blood, long feathered arms, metal claws, and a face made up of interlocking geometric patterns, topped with curled ram’s horns. Yet despite the reader’s knee-jerk reaction to label Pet as a monster, Pet insists that it is not a monster, but has come to Lucille to hunt monsters. Subsequent actions in the novel prove this to be true.

Indeed, monsters can not be identified simply by their appearance. How unsettling.

Even more unsettling are the next questions that the reader asks. If monsters can not be identified by their appearance then where did these preconceptions about monsters come from? Why are they so prevalent? What are the effects of these assumptions on our understanding of good versus bad? How might faulty assumptions contribute to a collective consciousness that is in itself monstrous?

These are all really heavy-hitting questions and completely appropriate for young adults as they are grappling with their world. But what about the adults? Aren’t we likely to be more deeply entrenched in the mire of the collective consciousness than teens and young adults who we credit with existing in a state of becoming? Isn’t it equally, if not more, important for adults to examine the constructs that form their thinking and upon which they base their assumptions? In order to be socially responsible members of our communities, don’t we need to closely examine our own biases? Pet confronts the reader with these questions and provides a context in which to examine them.

- Pet holds the reader accountable for the role they play in perpetuating society’s monstrous acts.

In reading Pet, I was struck but the way Emezi simultaneously creates a realistic, albeit quasi-magical, reality free of many of today’s social problems and holds the reader accountable for the role they play in perpetuating society’s monstrous acts. The novel provides a safe zone for the reader to grapple with their own degree of complicity and determine if they are brave enough to work, like Jam, to eradicate the monsters that lurk in their community.

Throughout the novel, there are sagely prophetic comments made by both the narrator and Pet. Warnings such as:

| Forgetting is dangerous. Forgetting is how the monsters come back. ~Akwaeke Emezi, Pet, p.20 |

and:

| Knowing, you think it gives you clarity, sight that pierces. It can be a cloud, a thing that obscures. ~Akwaeke Emezi, Pet, p.93 |

The reader knows that monsters have been allowed to return to Lucille because the danger has been forgotten and the fear has abated. This very real, very human tendency to forget or minimize the significance of past events is the source of many monstrous acts, both in the fictional town of Lucille and in the real world. Readers are confronted with this unpleasant truth and challenged not to fall victim to it.

However, the carelessness of forgetting is far from the most egregious offense to which the adult reader finds themselves connected. When Jam and her friend succeed in identifying the monster, the adults, who in all other ways seem to love, respect and cherish the kids of Lucille, refuse to accept the truth of the monster’s identity.

At points in my reading of Pet, I was a little uncomfortable. There was a prickling, tingling, nagging on my consciousness. Something was there and it needed to be examined and acknowledged. And so I did. My thoughts went something like this:

When we adults are confronted by hard or unpleasant truths is our first instinct denial? Why? Are we still holding on to the idea that we know what monsters look like? Does this prevent us from seeing the monstrous acts that are the true litmus test for monsters? If our belief in our ability to distinguish the good from the bad is shattered, then what other beliefs must we also re-examine? Where else might we be complicit in the perpetuation of monstrous acts due to our carelessness or our willful ignorance?

And, maybe most importantly, from where or from whom did the untruths originate, and why?

The discomfort of these questions is significant and important. Emezi’s novel provides a safe place in which to contemplate them and begin to address our own degree of complicity.

- Pet reveals the importance of truths, deep-seated truths, whose revelations are painful but are necessary in order for true healing to occur.

While it might be tempting to ignore what this novel has to offer because of the serious questions it raises for the adult reader, you really have no choice but to read it now. Walking away would, after all, be an act of complicity.

But let me put your mind at ease.

Be assured that this novel is far from doom and gloom and Emezi’s delivery is far from alienating. A majority of the novel is warm and inviting and the story ends on a hopeful note, despite the fact that:

| Humans take too long to see the truth. ~Akwaeke Emezi, Pet, p.172 |

Overall, Pet is a reinvestment in the belief of humanity’s capacity to change for the better. Truths are sometimes difficult, and the most important truths are the most painful ones to confront. Yet, in working as a community to dismantle the untruths and misinformation in our collective consciousness, we have the ability to reconstruct society on a foundation of truth rather than ignorance and begin to heal the wounds that have, up to this day, been festering.

The feeling I had when I finished reading Pet reminded me of when, as a teen, I got my first pair of eyeglasses. Up until that point I’d just been bumping along, doing my thing, seeing my world through near-sighted eyes. It was driving home from the eye doctor that I noticed for the first time the small print on street signs and was awed by the new clarity I had in perceiving my surroundings. These details had always been there, but up until that point I had not had the tools I needed to perceive them. Or, perhaps to make the analogy more accurate I should say that the tools I had used in the past were faulty. For me, reading Pet was another tool adjustment; I now wear bifocals.

Perhaps your tools are not faulty and when you read Pet you will not experience that prickling of new awareness. Perhaps you will just simply enjoy a well-written story about a courageous teen who seeks to make her world a better place. But, you won’t really know until you open the book.

And so, I ask you (the same question from the novel’s cover design): Are you brave enough to look?